08 Dec Can President Javier Milei inspire new life to Argentina’s slumping economy

Argentina President Javier Milei, an anarcho-capitalist, has his work cut out for him.

Argentina is in the news, electing a new President, Javier Milei, who describes himself as an anarcho-capitalist. Murray Rothbard, a leading economist of the Austrian school, is credited with introducing the term anarcho-capitalist. Anarchism is a philosophical school which emphasises human liberty and capitalism on free markets and private property. Anarcho-capitalism means that all the economic transactions will be done through voluntary agreements between individuals. The entire chain of economic activity will be coordinated by individuals and one neither needs government nor association of people to manage any economy.

Given Milei suggesting he is an anarcho-capitalist, there is a lot of discussion on how he will push Argentina towards individual liberty, free markets, abolish central bank, dollarise the currency and so on. It is really interesting that Argentina’s economics which has been an anarchy of sorts and moves from one extreme to the other, has a self-proclaimed anarcho-capitalist at the helm!

Before discussing Milei’s fiscal policies, we need to understand Argentina’s economic history.

Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice wrote the song “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” for the movie Evita. The movie Evita was based on the life of Eva Peron, the First Lady of Argentina, who was highly popular especially among working class people. The song was written as a way to communicate to Argentines to not mourn her as she never left them. While the soul of Eva Peron may have never left Argentina, the ghosts of her husband President Juan Peron’s economics, also labelled as Peronism did not leave them as well.

Argentine Economy Over the Years

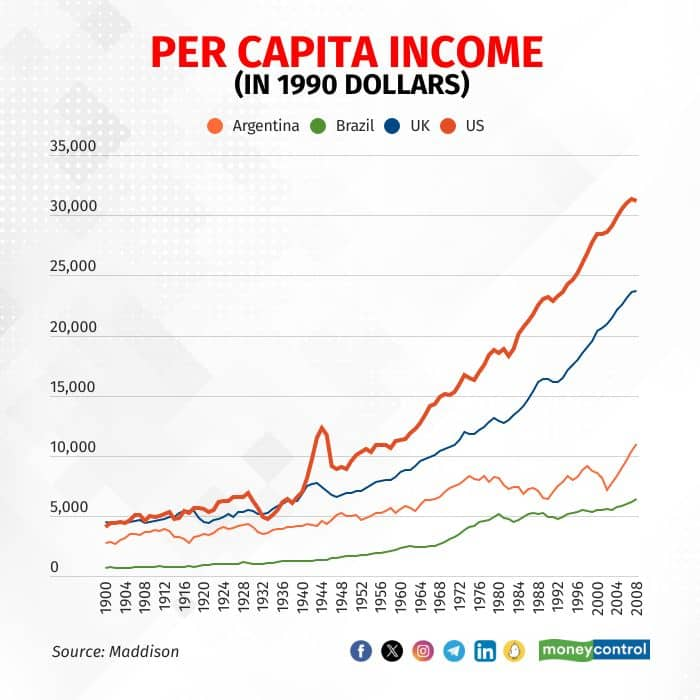

In the beginning of the 20th century, Argentina was categorised as one of the rich developed economies. The graph shows how the gap between Argentina and US/UK widens over the last 120 years.

The major factor for the decline is political instability. The country has alternated between multiple army coups and democracy. Even during periods of democracy there has been high instability with parties toppling each other’s governments. The political instability has in turn fueled economic instability. Even within economic policy, the country keeps oscillating from state controlled economy to free market economy with both resulting in equally disastrous consequences.

Story continues below Advertisement

The idea of state-controlled economy was given by Juan Peron who became President of Argentina from 1946-55 and then again during 1973-74 before his demise. Peronism is a combination of national-populism and national-socialism where the State plays a major role in coordinating economic activity between business and people. Oxford Reference defines Peronism as “an ill‐defined Argentinian political ideology, also known as justicialismo, which espouses Juan Perón’s policies of social justice, economic nationalism, and international non‐alignment.” Peronism failed to achieve any economic progress but despite its failures continues to be in memories of Argentine people and its politics.

The free market-oriented policies were tried in early 1990s, post the fall of the Berlin Wall and breakup of USSR. However, the outcomes were not very different from the earlier Socialism era as the efforts were botched by politics and short-term planning. The end result was Argentina faced huge economic crises in the 1990s and 2000s. The crisis led to changes in government and promises of going back to Peronism but the outcomes were not any different. The economy is caught in this vicious circle of political instability and crisis.

Effect of Political Instability

One way to understand this vicious circle is to see Argentina Central Bank. The central bank was established in 1935. In its nearly 90 year history, the central bank has had 61 Governors excluding the current Governor. This means an average term for the Governor has been around 1.5 years. Just for comparison sake, RBI established in the same year has had 25 Governors.

Of the 62 Governors, 21 Governors have been replaced within a year and 23 Governors have served for one year. Just three Governors have served a 5 year term, one has served a 6 year term and the founding Governor has served a 10 year term.

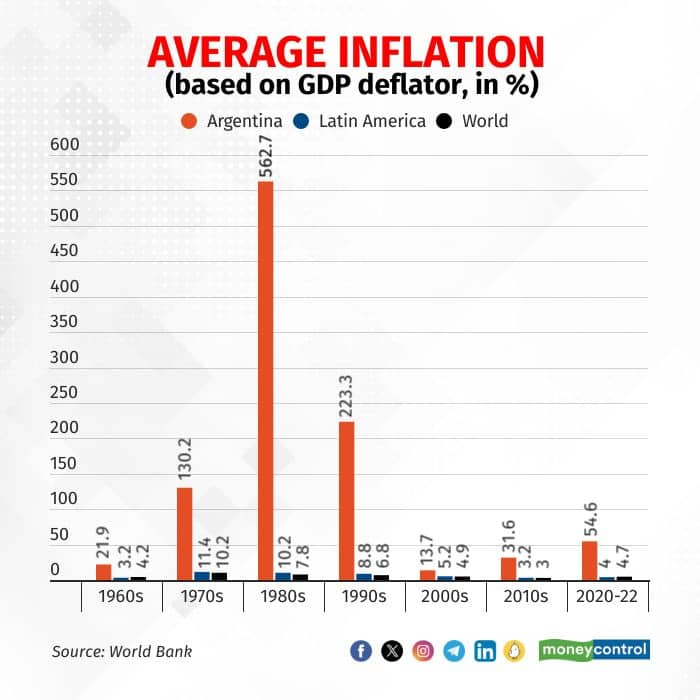

The frequent changes in Governorship is due to political instability as the new leaders have replaced Governors. The monetary policy has always been under the shadow of fiscal policy with the main purpose of financing government expenditure and deficits. The final outcome has been that the country has suffered from regular bouts of high and hyperinflation (table 2). Even currently, inflation is running above 100 percent levels.

Coming back to Milei, it is no surprise that one of the first thing he wishes to do is control inflation. Milei has announced that he will abolish the central bank and adopt the US dollar as Argentina’s currency. Abolishing the central bank and adopting dollarisation would mean that Argentina’s monetary policy can no more be manipulated by the central bank.

Milei Plans to Restructure Economy

Given Argentina Central Bank’s history and mismanagement of currency one cannot fault Milei for suggesting this policy. However, this is not the first time a newly elected politician has tried to reform Argentina’s monetary policy and lower inflation. Just like Milei, previous Presidents such as Carlos Menem and Mauricio Macri tried reformation policies but it only led to more misery. In the 1990s, Argentina adopted an arrangement named Currency Board which was hailed as a major reform. But it only lead to another bout of hyperinflation and misery.

While trying to understand Argentina’s continuous tryst with political instability and high inflation, one goes back to Germany’s hyperinflation. The year 2023 marks 100 years of Germany’s tryst with hyperinflation. The memories of hyperinflation are so deeply entrenched in the German mind, that they do utmost to avoid inflationary outcomes. Post Second World War, Germany (West) established a new central bank named Bundesbank which ran monetary policy in a way that it became a standard for other central banks. Even when European countries adopted a common monetary policy, the European Central bank was closely modelled on Bundesbank.

We don’t see any such concern in Argentina. Unless we see cultural changes within the Latin American nation, these new adventures of Argentina’s new President could only lead to more misadventures.

Amol Agrawal teaches at Ahmedabad University, and is the author of ‘History of Private Banking in South Canara district (1906-69)’. Views are personal, and do not represent the stand of this publication.