05 Apr Lost decade for the world economy?

The world growth rates were driven by emerging markets and developing economies, but we are seeing almost halving of the growth rates from 6 percent levels in 2000-09 to 3.2 percent levels in 2020-24.

The World Bank has been in news for the last one month. The nomination of Ajay Banga as the next President of the World Bank by the US President led to a frenzy of media articles. Before this frenzy could die down, the World Bank economists have released a book titled ‘Falling Long-Term Growth Prospects: Trends, Expectations, and Policies’. The book’s findings have caught attention for its pessimistic outlook on the world economy.

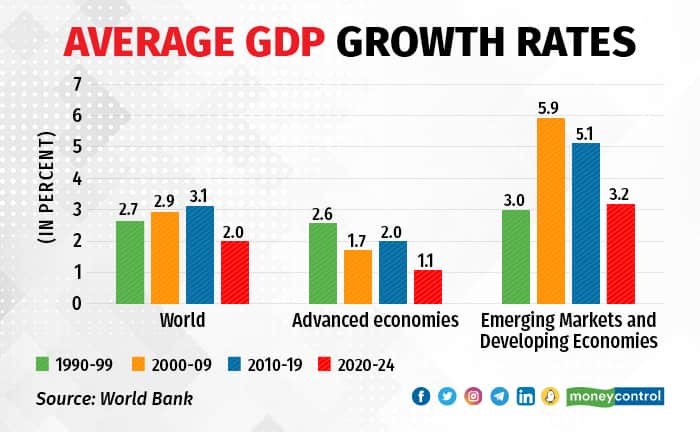

The outgoing World Bank President David Malpass in the foreword to the book notes: “The overlapping crises of the past few years have ended a span of nearly three decades of sustained economic growth”. In the graph below, we see that average decadal growth rates have declined in the 2020-24 decade compared to the previous three decades. The world growth rates were driven by emerging markets and developing economies, but we are seeing almost halving of the growth rates from 6 percent levels in 2000-09 to 3.2 percent levels in 2020-24. The share of countries with slower growth than in the previous decade has increased to 73 percent in 2010-21 from 44 percent in 2000-10.

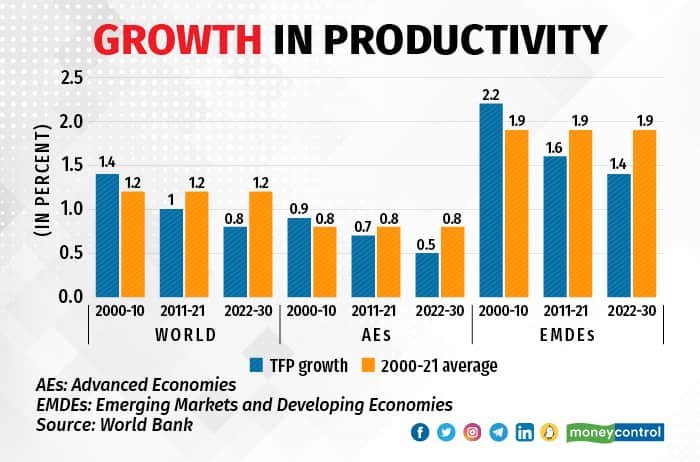

The authors of the book show that potential growth rates have declined from 3.5 percent in the 2000s to 2.6 percent in the 2010s and is expected to be even lower at 2.2 percent in the 2020s. The potential growth rates have declined due to a decline in productivity and we are seeing a decline in productivity for both advanced and emerging economies, as shown in the graph below. The decline in productivity in turn is due to poorer investments in physical capital, human capital, technology and so on. The pandemic certainly played a role in slowing investments in productivity, but the trends had started even before the pandemic.

In nutshell, the book is suggesting that the outcome of slipping growth, investments and productivity could be a lost decade for the world economy. There is a need for a big and broad policy push to rejuvenate the slowing world economy. The report highlights a few measures for restarting the growth engine.

The Prescription

First, increasing investments. Investments are key to increasing productivity which will translate to higher growth. However, these investments need to be aligned with climate goals. We should not invest in sectors which may lead to higher growth and higher carbon footprints. The reforms should focus on easing the doing of business, efficient labour markets, deepening the financial sector, etc.

Second, aligning monetary and fiscal policies. The policies should help moderate the business cycles. If monetary policy is tightening, a tighter fiscal policy will only lead to a sharper decline in growth. Likewise, both policies being easy will lead to a larger boom. Apart from managing business cycles, the frameworks should instil investor confidence and lead to higher domestic and foreign investment, which in turn will achieve the first measure.

Third, cutting down costs of international trade. The international trade costs (which include costs of shipping, logistics and trade barriers) still remain high despite many years of international negotiations and talks on international trade. The countries which have higher trade costs should attempt to bring them down and align with countries having lower trade costs. The countries should also shift the trade towards lower carbon products.

Fourth, capitalising on services. As trade in goods has got intertwined in geopolitics, countries should focus on international trade in services. Exports of digitally delivered professional services as a share of total service exports increased from 40 percent in 2019 to 50 percent in 2021. The higher service orientation requires a renewed focus on education and skills, particularly language and digital skills.

Fifth, increasing labour force participation, particularly of women and older age workforce. The average global participation rate of women in the labour force is still three-fourths that of men. In some regions such as South Asia and Africa, the gap between men’s and women’s labour force participation rate is even higher. Just increasing the level of women in the labour force will boost economic growth in these regions, which in turn will boost world growth prospects. The share of older age people in the workforce can also be increased by retraining and imparting new skills.

Sixth and finally, boosting global cooperation, without which all the above-listed efforts will be futile. One of the major factors for high global growth in previous decades was higher global cooperation. After the 2008 crisis, global cooperation started declining and is under serious stress post the pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine war. Trade costs have risen largely because of these ongoing disputes and lack of cooperation. The conflicts have made countries turn inwards and protectionist, undoing years of political and economic progress. The report categorically says that we need new effective methods of cooperation across forums: trade, climate, finance, debt transparency, fragility, health and infrastructure. Then only will we be able to mobilise the investment to achieve sustainable growth and poverty alleviation.

To sum up, the book by World Bank economists presents a bleak outlook for the world economy. The phrase ‘lost decade’ was first used for Japanese economy. Puja Mehra used the phrase for the Indian economy during 2008-18. The problem is that the lost decade, which is attributed to a particular decade, does not just stop at that one decade. The decline in economic prospects can continue as we have seen in the case of Japan which has had three decades of the lost decade and is in the fourth such decade! Indian economy is growing faster compared to the rest of the world but the growth rates are lower than in the decade of 2000s. Ajay Banga clearly has his job cut out. He does not just have to restore the lost prestige of the World Bank but also convey to its member economies that if we do not act, the world economy will face a lost decade.

Amol Agrawal is faculty at Ahmedabad University. Views are personal and do not represent the stand of this publication.